Book Notes pages 31-40 Springs, Windmill Hill

Page 31 - Swallowhead Springs

Because the name Swallowhead appears on so many old maps, it has been claimed that the spring must be a pre-Christian holy well, so revered that its name has survived to the present day. However the only evidence for this comes from Stukeley, who described Swallowhead as "the true fountain of the Kennet, which the country people call by the old name, Cunnit, and it is not a little famous among them. This is a plentiful spring." (Abury Described, p.19) Stukeley also noted that "apium grows plentifully about the spring-head of the Kennet. … To this day the country people have a particular regard for the herbs growing there, and a high opinion of their virtue." (Abury Described, p. 44) Stukeley is presumably referring to Apium nodiflorum or 'Fool's Watercress' which still grows profusely all along the River Kennet. It has no medicinal properties and though edible, it has no flavour.

Note: In The Silbury Treasure p. 114, Michael Dames refers to the tradition of curing eye complaints with water from holy wells, and suggests a connection with apium, once used to treat eye infections and other ailments. But the apium herb used medicinally was Apium petroselinum, or 'edible parsley', which does not grow at Swallowhead.

It has been suggested that the name 'Swallowhead' may originate from 'swallet' - a natural hole in the ground sometimes filled with water. But water usually flows in to swallets, not out of them; there are no such holes in the area anyway. It is possible though, that there may once have been a swallet where a stream passed below the ground for some distance, as we still see today around Winterbourne Bassett. Several locals recall hearing an unknown hydrologist, on an unknown BBC Radio 4 programme in the early 2000s, declare that a swallow spring is one "not fit for human drinking but acceptable for animals or for washing". Unfortunately I can add nothing to this and have found no references to a 'swallow spring' anywhere else.

The 'kink in the Kennet' between Pan Bridge and Swallowhead was likely connected to the construction of water meadows. In the Silbury area water meadows are poorly-recorded but their traces can still be seen. The first water-meadows on the River Kennet appeared at Ramsbury, east of Marlborough, sometime in the 17th century; they were modelled on prototypes constructed in the Wylye Valley, south Wiltshire, in the 1620s. Water-meadows were expensive and difficult to manage but were profitable because they increased sheep production. Once farmers realised this, water-meadows became standard practice. Their careful construction sometimes required plans to be drawn - is that how the swallow-like shape of the redirected River Kennet became apparent? Stukeley recorded the name Swallow-head in the 1720s; by then the area north of the springs could have been water-meadows for seventy years or more. The origins of the name may already have been forgotten.

Stukeley claimed he was told by locals that the spring was once "much more remarkable than at present, gushing out of the earth, in a continued stream. They say it was spoil'd by digging for a fox who earth'd above, in some cranny thereabouts; this disturb'd the sacred nymphs, in a poetical way of speaking." (Abury, p. 44) If Stukeley's tale is true, this may be an indication that the waters rise (or once did) under pressure, rather then simply seeping out when the water table rises to ground level; this may have been disturbed by the widening of the outlet, thus reducing the pressure.

Swallowhead Springs Map Notes

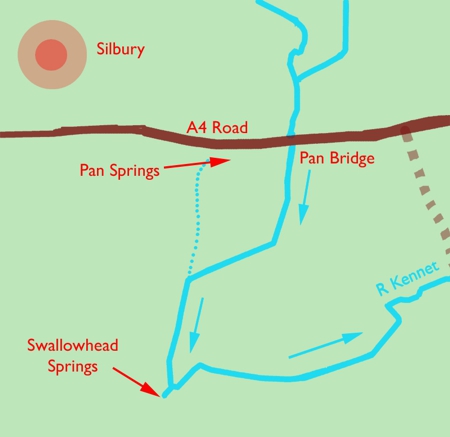

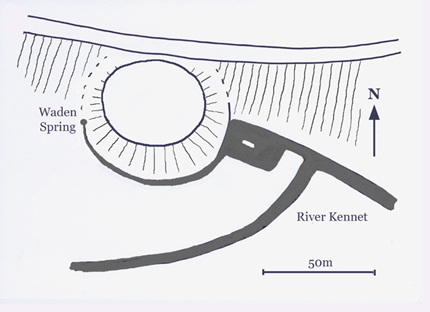

Left: The area around Swallowhead today, showing flow

The River Kennet has been canalised between Avebury and East Kennett. Instead of its natural route, it has been forced into a narrow channel and, in places, moved to a new course around the edge of fields that is on higher ground. Skillful water-engineering has thus increased the amount of land that is available for pasture. When was the river canalised?

South of Pan Bridge the River Kennet has been redirected westward to meet a south-flowing ditch that carries away water from the wide-spreading Pan Springs. The combined stream continues south until it meets the Swallowhead Springs, which are concentrated in a very small area. Boosted by the springs, the Kennet makes a sharp turn to flow eastward and eventually join the Thames. The westward kink in the Kennet's course is man-made - from Pan Bridge the river should naturally flow due south, to meet the eastward stream from Swallowhead.

The name 'Swallowhead' may refer to the shape of the canalised river, as when shown on a map it appears similar to the head of a swallow. The area in question was used to create artificial water meadows and relocating the river was likely part of that work.

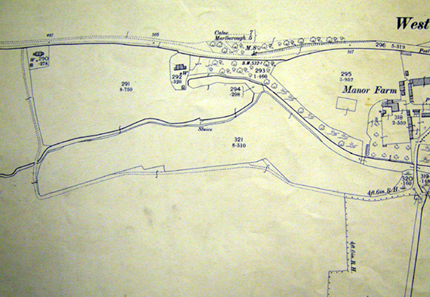

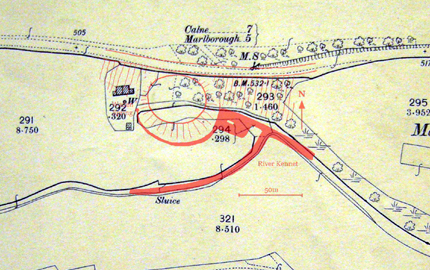

Left: The Ordnance Survey map of 1898 shows the River Kennet to be exactly where it is today, following its man-made route around Silbury to Swallowhead.

.jpg)

Swallow on the West Kennet long barrow.

For more information and maps of the water meadows of the Swallowhead area, see pages 276-9 of the monograph Silbury Hill: The Largest Prehistoric Mound in Europe, 2013, English Heritage.

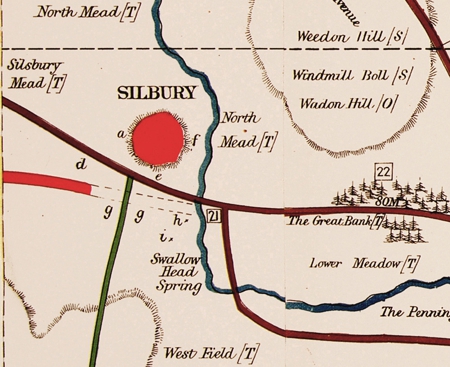

Left: Andrews & Dury's map of 1773 was unusually accurate for its time and was later used as the basis for Ordnance Survey maps. It also shows the River Kennet's route from Avebury to Silbury to be the same as today's. The only difference is a bifurcation at Aubury Bridge where the river crosses under the road as two streams. Traces of the second stream may still be seen today.

However, the arrangement of rivers around Swallowhead is quite different. From Pan Bridge the Kennet's main flow is shown to be slightly to the east of due south - its natural route - without the westward kink. The south-flowing drain from the Pan Springs is shown to end at a large pool at Swallowhead. Several writers have described a pool there.

There is good reason to suspect that Andrews & Dury did not depict the Swallowhead Springs accurately, since the river's westward kink was almost certainly in place by 1773. Was the true course masked by a maze of river channels through the water meadows? The mapping may also have been done in summer, when the river and springs were dry.

Note that the Swallowhead Springs are the only ones indicated - as with later maps, the Waden and Pan Springs are not shown.

Left AC Smith's map, published in 1884, was hand-drawn at the huge scale of six inches to the mile. Although Smith's book describes a pool at Swallowhead, it is not shown on the map.

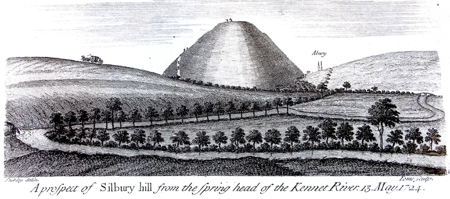

Left: William Stukeley's engraving was published in 1743, some twenty years after his visits to Avebury. The pool at Swallowhead is clearly shown, and for the first time, the kink in the Kennet is apparent.

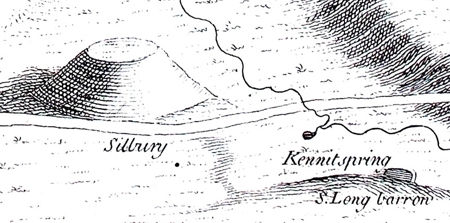

Left: Stukeley's 1724 sketch was probably made in the field. The Swallowhead pool is shown, but the kink in the Kennet is not.

As the 1743 engraving below shows, Stukeley was certainly aware of the Kennet's true course from Pan Bridge to Swallowhead. Comparing his drawing with the modern Ordnance Survey view below it shows just how accurately he depicted it.

Finally, at the bottom of the page is a blown-up portion of Stukeley's engraving. Uniquely, it appears to show the Swallowhead Spring in action, but note that its waters are flowing into the river - there is no pool.

Stukeley's 1743 engraving clearly shows the kink in the River Kennet.

Compare with today's OS map below

.

.

Magnified section of Stukeley's engraving showing the Swallowhead Springs flowing into the Kennet.

Page 31 - Waden Springs and 'Silbaby'

The Waden Spring emerges from several holes in the base of a large mound of soil and rubble that has been tipped from the road above. The mound, dubbed 'Silbaby', resembles Silbury Hill and for a time was considered as possibly prehistoric. This has now been disproved, but the mound's origins are still a mystery. Fine flint gravel can be seen where the springs emerge - residue from chalk dissolved by rainwater. Just east of the spring, the water flows through a rectangular pond and on into the Kennet.

Although the Waden Spring usually dries up each summer, in wet weather it will usually flow more vigorously than Swallowhead. As such times, bubbles can be seen in the pond, where springs rise from below. There are many springs flowing into the pond from all along the eastern side of the mound. Some rise from beneath the pond; others flow directly from the base of the mound itself. It is clear that the mound sits directly on top of an area of very active springs. Water from the pond flows east into the River Kennet. In the winter of 2012-13 though, so much water flowed from the spring that it saturated the field south of the mound and flowed straight into the Kennet, as well as following its usual eastward channel. At 10°C the overflowing water melted through the January snow.

Between the mound and the River Kennnet some of this excess water accumulated in lenses beneath the turf, producing a 'wobbly field' as can be seen in this video:

WOBBLY FIELD VIDEO

The Mystery of 'Silbaby'

Above: My 2010 survey of Silbaby

Above: The 1900 edition Ordnance Survey map, at a scale of 6" to the mile, shows that there was no mound on top of the Waden Springs at the start of the 20th century. In the top left is the house that survives today, alongside the track to the WK long barrow. In the top centre, just west of the springhead, is a pair of cottages; named 'Mount Pleasant' they are long gone. Note that the cottages share a well and outside toilet.

Above: My Silbaby plan superimposed on the 1900 Edition OS map. It shows that springs rise today on the western side of the mound, exactly where the (now buried) springhead channel once began its eastward flow.

Above: Silbaby seen from a balloon.

In 2006 Pete Glastonbury discovered a large earthern mound, less than half a mile east of Silbury, on the south side of the A4 road. Surprisingly, the mound had never been noticed before, despite its prominent location in a World Heritage site.

With its flat, round top and sloping side, the mound resembled a scale model of Silbury and was jokingly dubbed 'Silbaby' - a name that stuck.

Ref: Mortimer, N. 2006. "Silbaby Hill." Fortean Times. Issue 206. Feb 2006

There was speculation that the mound might be prehistoric - could it have been a prototype for Silbury?

I roughly surveyed Silbaby in early 2010 using GPS and measuring tapes (see my map opposite). Silbaby was shown to be elliptical, its long axis aligned east-west. Its sides are not entirely round and have some almost straight sections, as do Silbury's. The base of Silbaby measures approximately 76m by 68m; its top is approximately 47m by 37m and level to within a metre, despite all the rubbish that has been dumped there, At 11m high, its shape is a much shorter truncated pyramid than Silbury. The slope of Silbaby's southern side is around 34 degrees.

The Waden Springs rise in several places around the mound - chiefly from a single point on the western side and from beneath the rectangular pond on the eastern side. Superimposing my plan on the 1900 Edition OS map reveals that these two positions align with the wide, east-flowing springhead channel that once was there. It seems that the mound was sited on top of some very active springs.

Silbaby's size and proportions were similar to the Marlborough Mound ('Merlin's Mound'), whose age was unknown at the time. Then in 2010 archaeologist Jim Leary conducted a coring survey of the Marlborough Mound: it was carbon dated to 2300 - 2040 BC, the same age as Silbury. MARLBOROUGH MOUND REPORT

Leary then cored Silbaby (now more respectably renamed 'The Waden Mound'). When carbon-dated, the core samples showed it to be:

"A post-medieval feature (around sixteenth/seventeenth century AD), and not prehistoric. The dates came from a series of locations throughout the mound, including near the base, so I don't think there is much doubt. On the plus side, they are archaeological at least and it should have been there in Stukeley's day. The next question of course is - what is it?" Jim Leary, Pers Comm.

That question has not yet been fully answered. The mound is made of layers of rubble, dumped from the A4 road above. The A4 road was once a busy coaching route from London to Bath - perhaps rubbish from the 16th & 17th centuries was accidentally mixed with rubble, and dumped during a road-widening episode in 1960? This seemed the most plausible explanation until aerial photographs were discovered, showing that the mound was already there in the late 1940s.

The Cambridge University Collection of Aerial Photographs (CUCAP) has several pictures of the area around Silbury

Picture LL70 from April 1953 shows the Silbury ditch 'dry' but with an amount of surface water on the fields. The 'dump' can be clearly seen, partly scrubbed over to the mid-left. (click image for a close-up)

There is also a shot from 1947 (not included here) that just clips the area, but shows that the 'dump' is present and partly vegetated. Thanks to Steve Boreham for tracing these pics. So although rubble may have been dumped in 1960 when the A4 road was widened, dumping must have started at least several decades before then. Was it military? Could it perhaps have been connected with the construction of RAF Yatesbury?

Page 36 - The Old Kennet

Phillipe Ullens' aerial photo of Avebury, taken looking NE, perfectly illustrates how today's managed River Kennet reverts to its wide-spreading prehistoric course when water levels are high. For extra clarity the flooded areas shown in Phillipe's photo have been added to this 3-D Ordnance Survey map image, which matches the photo: OS MAP AVEBURY FLOOD

Page 36 - Windmill Hill

This downloadable Google Earth kml file contains an overlay plan of the Windmill Hill earthworks. The three rings are shown as paths, and the positions of the nine round barrows as placemarks. WINDMILL HILL kml

As a gpx file, the same information may be loaded into a hand-held GPS or mobile phone. The three earthwork rings and some of Windmill Hill's round barrows are difficult to see on the ground, but with the help of GPS it is possible to make them out. You can convert kml files to gpx files here.

Page 37 - Bayesian Dating

When Presbyterian minister Thomas Bayes solved the mathematical problem of 'inverse probability' in the 18th century, his interest was largely philosophical. Since the advent of computers, Bayes' Theorem has found countless application in statistics, medicine and spam-filtering; the latest is in archaeological dating. Gathering Time reports the results of a huge dating programme which is set to revolutionise archaeology, re-writing as it does the Early Neolithic in Britain. Several thousand Radio-Carbon (RC) dates from 38 enclosure sites across Britain have been analysed, producing chronologies of previously unimagined accuracy. RC dating, even when calibrated against tree-ring data, produces a 'scatter' of calendar dates that can span many centuries; Bayesian Statistics can refine these into steps of around 25 years - just one human generation - or even less.

The Bayesian dates are expressed as probabilities - the broader their span, the higher the probability. So the excavation date of the first ditch to be dug at the Windmill Hill enclosure is given as '3700-3640 cal BC (95% probability), probably in 3680-3650 cal BC (68% probability)'. Dates are given for the start and end of construction of each site in the study, usually considering its various components separately. Windmill Hill's three concentric earthworks are now known to have been dug in an odd sequence: first the inner ditch, then the outer, finally the middle - the entire process taking around 50 years. The enclosure continued to be used for over 300 years, yet other sites were abandoned after only a generation or so.

Page 38 - Windmill Hill References

Keiller's excavations of Windmill Hill went unpublished until after his death, when Isobel Smith was comissioned by Keiller's widow to produce a book:

Smith, I.F. 1965. Windmill Hill and Avebury. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

In 1998 Alasdair Whittle conducted some excavations of Windmill Hill, which were reported in:

Whittle, A., Pollard, J. and Grigson, C. 1999. The harmony of symbols: the Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

See also: Gillings, M. and Pollard, J. 2004. Avebury. London: Duckworths.